To a Great Egret, Tomales Bay is full of food, but that food is not always available. Every two weeks, around the new and full moons, the lowest tides and the greatest foraging opportunity coincide with the early morning, making breakfast on the bay an easy affair. During low tides, hundreds of acres of intertidal eelgrass are exposed, allowing egrets to stab at herring during spawning events or to hunt pipe fish, which try to wrap themselves around the egret’s bill to avoid being swallowed. As the tide cycle shifts and morning tides become higher, the eelgrass is exposed for fewer hours per day, reducing foraging opportunities on the bay. During these times, egrets switch to inland ponds and creeks to hunt small fish or walk the surrounding pastures in groups to capture rodents.

In June 2017, ACR’s team at the Cypress Grove Research Center put Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite tags on three Great Egrets (described in the Ardeid 2017). While we already knew that Great Egrets on Tomales Bay alter their behavior with the tides, we didn’t realize how in-tune with tidal cycles they are until we began using GPS tags to study the movements of individual birds.

When on the bay, they spent the mornings chasing prey along the shallow mud flats, following the tide in and out to match their preferred water depth of about 20–30 cm. When inland, they sought creeks and farm ponds, periodically roosting in tall patches of trees. When the tides transitioned to a more extreme part of the cycle, with eelgrass beds exposed earlier in the morning, they returned to Tomales Bay.

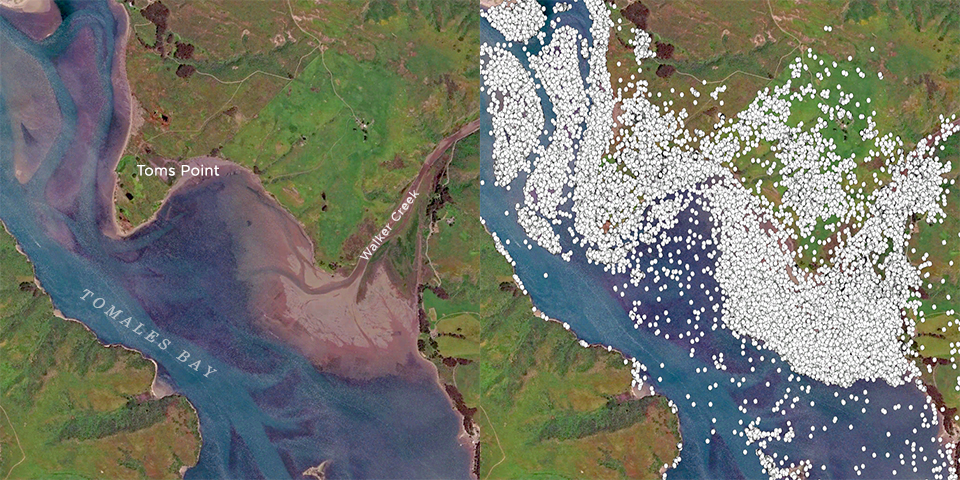

The image above—a slice of northern Tomales Bay—shows how Great Egrets use the bay’s eelgrass beds and shallow mud flats in their foraging activities. The image on the left reveals the deep channels winding between shallow eelgrass beds (dark areas) and unvegetated mud flats. The image at right shows all GPS points logged by any of our tagged birds from June 2017 through Nov 22 of this year.

This is just one interesting discovery we’ve made in the first year of tracking these majestic birds. More insights are revealed in the new issue of the Ardeid, ACR’s journal of Conservation Science. Article and graphs by ACR Avian Ecologist David Lumpkin. The article begins on page 10 > https://egret.org/sites/default/files/acr_ardeid_2018.pdf