|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Recent black bear sightings in the North Bay bring excitement and curiosity about what it means now that our wild neighbors are back.

If you spend time in Marin, Napa, or Sonoma counties, you may have heard about an increase in black bear sightings over the last several years. Most people don’t think of bears when they think about coastal California, even though bears have roamed beaches, fir forests, scrubby woodlands, and chaparral for thousands of years.

With increased sightings of black bears in the North Bay, many people and organizations are wondering if we have the infrastructure and educational resources to help people coexist happily with black bears. This warrants bigger questions like what does it mean to coexist with black bears and is it possible to strengthen a shared “bear culture” in the North Bay?

Historically, black bears existed in Sonoma and Marin counties for thousands of years

Black bears are omnivorous mammals whose fur ranges in color from tan to cinnamon to black. Much of their diet consists of acorns, berries, insects, grasses, forbs, as well as meat–when its available. Black bears are smaller than grizzly bears and solitary creatures, except when sows are raising cubs.

In 1924, the last grizzly bear sighting occurred in California. Since then, black bears have been the only bear species found in the state. For ecologists and conservationists like Meghan Walla-Murphy, who helps lead the North Bay Bear Collaborative (NBBC), the return of black bears in higher numbers is exciting. Cub sightings also make Meghan excited.

“So many of our ideas about black bears come from the media, which often highlight worst case scenarios,” Meghan explains. “Growing a ‘bear culture’ in the North Bay means sharing other narratives around bears so we can remember what it is like to live among large mammals with less conflict and more coexistence.”

In addition to the cultural shift, there is a scientific need for more data, especially with more cub sightings.

“Cubs are a great sign, because it means there is a residential and reproducing bear population within Sonoma County. After thousands of years of living without grizzlies and decades of fewer sightings of black bears, cubs are a big deal.”

Research helps determine North Bay bear population

Last year, the DNA sampling found evidence of 33 individual bears roaming across 4 study areas in the Mayacamas: Sugarloaf Ridge State Park, Modini Preserve, Pepperwood Preserve, and the Dunn-Wildlake Preserve in Napa County. With our wild neighbors returning to the North Bay and growing their population, we also have an opportunity to be proactive about preparing our communities to coexist with black bears.

To develop a plan, wildlife ecologists and community members need to know how many bears call the North Bay home and what is the best way to educate the public about coexisting with black bears. An ongoing part of this means spending time in the field to install wildlife cameras, collect bear scat for DNA research, understand the ecosystems in areas with black bear sightings, and increase the educational campaigns about black bears.

Audubon Canyon Ranch’s two preserves in the 50-mile-long Mayacamas mountain range — Bouverie Preserve and Modini Preserve — are ideal for bear research. Their rural location and their surrounding wildlife corridors help connect pockets of habitat and the corridors also make great places for wildlife cameras.

Cameras at Modini Preserve began documenting wildlife in 2013

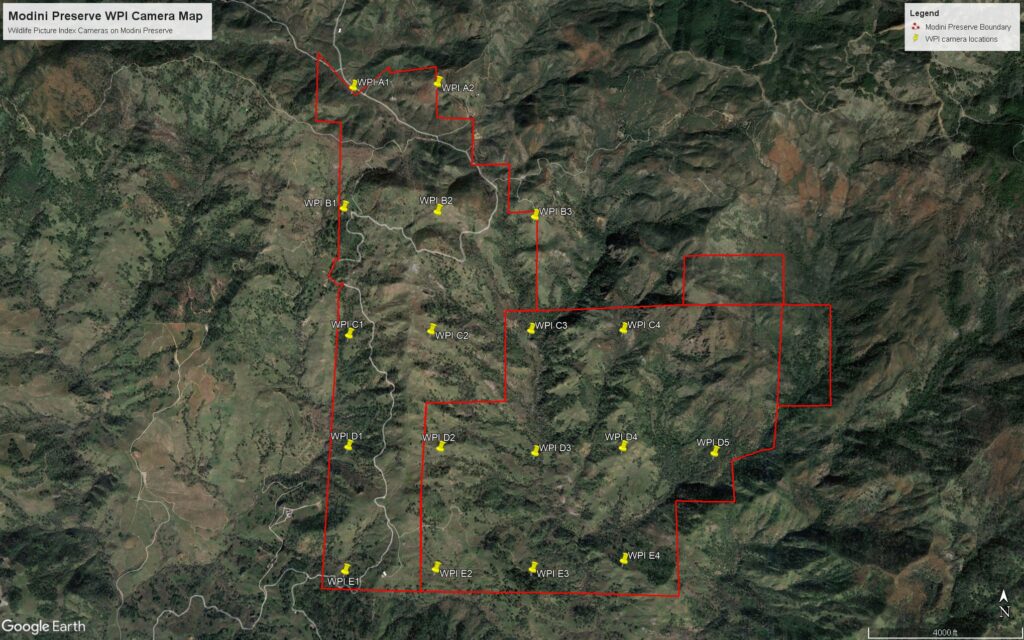

In 2012, Pepperwood launched the first Wildlife Picture Index Project (WPI) grid in North America, installing a series of trail cameras on its preserve northeast of Santa Rosa, California. In 2013, Pepperwood invited Audubon Canyon Ranch to join the project by setting up another camera grid, now totaling 18 cameras, on our nearby Modini Preserve.

With the two camera grids poised to capture wildlife within a few miles of each other, they might document movements of wide-ranging animals like mountain lions and black bears. These grids are essential for long-term data collection so stewards can make informed decisions about conservation priorities and land management.

“By collaborating on the Wildlife Picture Index, we get to learn from each other and share research,” Steven Hammerich, wildlife specialist at Pepperwood, adds. “As we continue to document wildlife, I also find myself asking even more questions like, ‘How are animals like black bears responding to wildfires and climate change — and what does this mean for greater conservation efforts?’ ”

In 2020, Meghan and volunteers with NBBC began collecting bear scat from the four study areas in the Mayacamas, including Audubon Canyon Ranch’s Modini Preserve, as an additional source of data.

“At first we wanted a population estimate, but we soon realized that our questions went far beyond ‘how many bears.’ For the past three years, we’ve been curious about how bears are related to one another, which can tell us about genetic bottlenecking and habitat fragmentation.”

2019 Kincade Fire brings new questions about bear habitat

Meghan contacted Michelle Cooper, the preserve manager and resident biologist, to collect bear scat from Modini Preserve. This was shortly after the Tubbs Fire in 2017 and before the Kincade Fire in 2019, which significantly altered the landscape.

“The burn intensity of the Kincade Fire on the preserve was highly variable,” Michelle explains. “Some areas burned very hot, incinerating all the existing vegetation, primarily on higher elevation ridges dominated by knobcone pine and chaparral communities. Now we’re seeing berry-producing shrubs like elderberry and manzanita mature enough to produce fruits again along with other foods that black bears eat.”

We do not know the fire’s effect on bears. For example, it’s possible that black bears are recorded more at the preserve now because the landscape around the preserve changed significantly after the fire and bears were attracted to the creeks that run year-round on Modini; however, this hypothesis and many others require more research.

Abundant rainfall over the last year may have also influenced the local bear population. Michelle notes that “We are coming off of a three-year drought after the fire. The rainfall over the last year helped the recovery of local flora, which in turn, may also be influencing the return of black bears to the area.”

After the 2019 Kincade Fire, the oak woodland understory on the preserve had no grass left and was covered in acorns. “I can’t help but think that those were good days for many acorn-loving critters,” Michelle adds, “although the immediate impact of that burn was hard to witness.”

The higher elevation ridges at Modini Preserve, where many of the berry and acorn-bearing shrubs and trees exist, are producing fruit again. “There is more bear food this year than in the last few years. Sightings, tracks, and scat are often found near water sources during the hot summer months.”

The implementation of smaller, prescribed fires at Modini Preserve may also influence the diversity of plant life – and bear food – but more research is needed.

“Bears ask us to be accountable for our messes, our food, and our shared land,” Meghan states.

One concern people have about living among bears has nothing to do with bears, as much as with human behavior — especially regarding trash and waste management. If you have camped in “bear country” before, you may be familiar with campground regulations that ask you to put all food in bear boxes. This line of proactive behavior will be increasingly important in certain North Bay residential areas too.

“We need proper infrastructure, educational outreach to our communities, and behavior change,” Meghan shares. “I’d love to see a future where trash collection is more efficient and where kids grow up knowing things like, ‘don’t put the trash out the night before!’”

There is another opportunity here for anybody who cares about conservation of wildlands: bears may prefer wild areas with diverse flora. “When bears have enough food and wild space to forage, we’re doing land stewardship right,” Meghan explains.

Additional goals of the NBBC are to educate the public about bears, to foster a deeper connection to bears via Tribal Youth Bear Projects, and to understand the concerns, ideas, and solutions that various community members have about black bears returning in higher numbers.

This third goal means offering physical and virtual meetings where proactive solutions can be created in partnership with local tribes, including the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians and Mishewal Wappo, as well as with nonprofits, wineries, private landowners, waste management facilities, state parks, and regional parks.

“We have a lot of people sitting down at the table for these meetings,” Meghan reflects, referring to the in-person and virtual meetings. “I’m honored to connect with people who care so deeply about our personal and ecological communities.”

Sharing data and conservation efforts across so many people and organizations helps sustain efforts toward long-term change.

“We are honored to be part of the North Bay Bear Collaborative and hopeful that the collective work across multiple parcels and partnering organizations such as Pepperwood and Sonoma Land Trust will have great impact,” Tom Gardali, CEO of Audubon Canyon Ranch, shares.

Learn more about coexisting with black bears

The North Bay Bear Collaborative connects people and various stakeholders so they can work together toward a shared bear culture. Following their newsletter and organizations they partner with is a great way to stay informed about the latest efforts to support our wild North Bay neighbors.

Here are three simple tips you can also do to stay bear-wise and move our culture toward one that respects — and values — black bears.

- Share this article with your neighbors and community members to spread awareness of the return of black bears and how coexisting among black bears is possible.

- Secure your food, garbage, and recycling bins. Visit bearwise.org for details on how to do this.

- Support conservation organizations like Audubon Canyon Ranch and the North Bay Bear Collaborative who are working to boost understanding of our local black bear population.